create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch

Building a 2.3M-parameter LLM from scratch with LLaMA 1 architecture.

Stars: 65

The 'create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch' repository provides a detailed guide on creating a Large Language Model (LLM) with 2.3 million parameters from scratch. The blog replicates the LLaMA approach, incorporating concepts like RMSNorm for pre-normalization, SwiGLU activation function, and Rotary Embeddings. The model is trained on a basic dataset to demonstrate the ease of creating a million-parameter LLM without the need for a high-end GPU.

README:

Making your own Large Language Model (LLM) is a cool thing that many big companies like Google, Twitter, and Facebook are doing. They release different versions of these models, like 7 billion, 13 billion, or 70 billion. Even smaller communities are doing it too. You might have read blogs or watched videos on creating your own LLM, but they usually talk a lot about theory and not so much about the actual steps and code.

This blog is a replicated and a bit more detailed blog of this REPO created by Brian Kitano

In this blog, I’ll try to make an LLM with only 2.3 million parameters, and the interesting part is we won’t need a fancy GPU for it. We’ll follow a LLaMA 1 Paper Approach to guide us. Don’t worry; we’ll keep it simple and use a basic dataset so you can see how easy it is to create your own million-parameter LLM.

- Prerequisites

- Understanding the Transformer Architecture of LLaMA

- Setting the Stage

- Data Preprocessing

- Evaluation Strategy

- Setting Up a Base Neural Network Model

- Replicating LLaMA Architecture

- Experimenting with hyperparameters

- Saving Your Language Model (LLM)

- Conclusion

Make sure you have a basic understanding of object-oriented programming (OOP) and neural networks (NN). Familiarity with PyTorch will also be helpful in coding.

| Topic | Video Link |

|---|---|

| OOP | OOP Video |

| Neural Network | Neural Network Video |

| Pytorch | Pytorch Video |

Before diving into creating our own LLM using the LLaMA approach, it’s essential to understand the architecture of LLaMA. Below is a comparison diagram between the vanilla transformer and LLaMA.

(Llama architecture by Umar Jamil)In case you’re not familiar with the vanilla transformer architecture, you can read this blog for a basic guide.

Let’s look into the essential concepts of LLaMA with a bit more detail:

In the LLaMA approach, a technique called RMSNorm is employed for normalizing the input of each transformer sub-layer. This method is inspired by GPT-3 and is designed to optimize the computational cost associated with Layer Normalization. RMSNorm provides similar performance to LayerNorm but reduces the running time significantly (by 7%∼64%).

It achieves this by emphasizing re-scaling invariance and regulating the summed inputs based on the root mean square (RMS) statistic. The primary motivation is to simplify LayerNorm by removing the mean statistic. Interested readers can explore the detailed implementation of RMSNorm here.

LLaMA introduces the SwiGLU activation function, drawing inspiration from PaLM. To understand SwiGLU, it’s essential to first grasp the Swish activation function. SwiGLU extends Swish and involves a custom layer with a dense network to split and multiply input activations.

The aim is to enhance the expressive power of the model by introducing a more sophisticated activation function. Further details on SwiGLU can be found in the associated paper.

Rotary Embeddings, or RoPE, is a type of position embedding used in LLaMA. It encodes absolute positional information using a rotation matrix and naturally includes explicit relative position dependency in self-attention formulations. RoPE offers advantages such as scalability to various sequence lengths and decaying inter-token dependency with increasing relative distances.

This is achieved by encoding relative positions through multiplication with a rotation matrix, resulting in decayed relative distances — a desirable feature for natural language encoding. Those interested in the mathematical details can refer to the RoPE paper.

In addition to these concepts, the LLaMA paper introduces other significant approaches, including the use of the AdamW optimizer with specific parameters, efficient implementations such as the causal multi-head attention operator available in the xformers library, and manually implemented backward functions for transformer layers to optimize computation during backward passes.

A special acknowledgment and thanks to Anush Kumar for providing an in-depth explanation of each crucial aspect of LLaMA.

We’ll be working with a range of Python libraries throughout this project, so let’s import them:

# PyTorch for implementing LLM (No GPU)

import torch

# Neural network modules and functions from PyTorch

from torch import nn

from torch.nn import functional as F

# NumPy for numerical operations

import numpy as np

# Matplotlib for plotting Loss etc.

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# Time module for tracking execution time

import time

# Pandas for data manipulation and analysis

import pandas as pd

# urllib for handling URL requests (Downloading Dataset)

import urllib.requestFurthermore, I’m creating a configuration object that stores model parameters.

# Configuration object for model parameters

MASTER_CONFIG = {

# Adding parameters later

}This approach maintains flexibility, allowing for the addition of more parameters as needed in the future.

In the original LLaMA paper, diverse open-source datasets were employed to train and evaluate the model.

Unfortunately, utilizing extensive datasets may be impractical for smaller projects. Therefore, for our implementation, we’ll take a more modest approach by creating a dramatically scaled-down version of LLaMA.

Given the constraints of not having access to vast amounts of data, we will focus on training a simplified version of LLaMA using the TinyShakespeare dataset. This open source dataset, available here, contains approximately 40,000 lines of text from various Shakespearean works. This choice is influenced by the Makemore series by Karpathy, which provides valuable insights into training language models.

While LLaMA was trained on an extensive dataset comprising 1.4 trillion tokens, our dataset, TinyShakespeare, containing around 1 million characters.

First, let’s obtain our dataset by downloading it:

# The URL of the raw text file on GitHub

url = "https://raw.githubusercontent.com/karpathy/char-rnn/master/data/tinyshakespeare/input.txt"

# The file name for local storage

file_name = "tinyshakespeare.txt"

# Execute the download

urllib.request.urlretrieve(url, file_name)This Python script fetches the tinyshakespeare dataset from the specified URL and saves it locally with the filename “tinyshakespeare.txt.”

Next, let’s determine the vocabulary size, which represents the unique number of characters in our dataset. Here’s the code snippet:

# Read the content of the dataset

lines = open("tinyshakespeare.txt", 'r').read()

# Create a sorted list of unique characters in the dataset

vocab = sorted(list(set(lines)))

# Display the first 10 characters in the vocabulary list

print('Printing the first 10 characters of the vocab list:', vocab[:10])

# Output the total number of characters in our dataset (Vocabulary Size)

print('Total number of characters in our dataset (Vocabulary Size):', len(vocab))Now, we’re creating mappings between integers to characters (itos) and characters to integers (stoi). Here’s the code:

# Mapping integers to characters (itos)

itos = {i: ch for i, ch in enumerate(vocab)}

# Mapping characters to integers (stoi)

stoi = {ch: i for i, ch in enumerate(vocab)}In the original LLaMA paper, the SentencePiece byte-pair encoding tokenizer from Google was used. However, for simplicity, we’ll opt for a basic character-level tokenizer. Let’s create encode and decode functions that we’ll later apply to our dataset:

# Encode function: Converts a string to a list of integers using the mapping stoi

def encode(s):

return [stoi[ch] for ch in s]

# Decode function: Converts a list of integers back to a string using the mapping itos

def decode(l):

return ''.join([itos[i] for i in l])

# Example: Encode the string "hello" and then decode the result

decode(encode("morning"))The final line will output morning confirms the proper functionality of the encode and decode functions.

We are now converting our dataset into a torch tensor, specifying its data type for further operations using PyTorch:

# Convert the dataset into a torch tensor with specified data type (dtype)

dataset = torch.tensor(encode(lines), dtype=torch.int8)

# Display the shape of the resulting tensor

print(dataset.shape)The output istorch.Size([1115394]) indicates that our dataset contains approximately one million tokens. It's worth noting that this is significantly smaller than the LLaMA dataset, which consists of 1.4 trillion tokens.

We’ll create a function responsible for splitting our dataset into training, validation, or test sets. In machine learning or deep learning projects, such splits are crucial for developing and evaluating models, and the same principle applies here in replicating a Large Language Model (LLM) approach:

# Function to get batches for training, validation, or testing

def get_batches(data, split, batch_size, context_window, config=MASTER_CONFIG):

# Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets

train = data[:int(.8 * len(data))]

val = data[int(.8 * len(data)): int(.9 * len(data))]

test = data[int(.9 * len(data)):]

# Determine which split to use

batch_data = train

if split == 'val':

batch_data = val

if split == 'test':

batch_data = test

# Pick random starting points within the data

ix = torch.randint(0, batch_data.size(0) - context_window - 1, (batch_size,))

# Create input sequences (x) and corresponding target sequences (y)

x = torch.stack([batch_data[i:i+context_window] for i in ix]).long()

y = torch.stack([batch_data[i+1:i+context_window+1] for i in ix]).long()

return x, yNow that our splitting function is defined, let’s establish two parameters crucial for this process:

# Update the MASTER_CONFIG with batch_size and context_window parameters

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

'batch_size': 8, # Number of batches to be processed at each random split

'context_window': 16 # Number of characters in each input (x) and target (y) sequence of each batch

})batch_size determines how many batches are processed at each random split, while context_window specifies the number of characters in each input (x) and target (y) sequence of each batch.

Let’s print a random sample from the train split of batch 8 and context window 16 from our dataset:

# Obtain batches for training using the specified batch size and context window

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Decode the sequences to obtain the corresponding text representations

decoded_samples = [(decode(xs[i].tolist()), decode(ys[i].tolist())) for i in range(len(xs))]

# Print the random sample

print(decoded_samples)Now, we are set to create a function dedicated to evaluating our self-created LLaMA architecture. The reason for doing this before defining the actual model approach is to enable continuous evaluation during the training process.

@torch.no_grad() # Don't compute gradients for this function

def evaluate_loss(model, config=MASTER_CONFIG):

# Placeholder for the evaluation results

out = {}

# Set the model to evaluation mode

model.eval()

# Iterate through training and validation splits

for split in ["train", "val"]:

# Placeholder for individual losses

losses = []

# Generate 10 batches for evaluation

for _ in range(10):

# Get input sequences (xb) and target sequences (yb)

xb, yb = get_batches(dataset, split, config['batch_size'], config['context_window'])

# Perform model inference and calculate the loss

_, loss = model(xb, yb)

# Append the loss to the list

losses.append(loss.item())

# Calculate the mean loss for the split and store it in the output dictionary

out[split] = np.mean(losses)

# Set the model back to training mode

model.train()

return outWe have used the loss as a metric to assess the performance of the model during training iterations. Our function iterates through the training and validation splits, computes the mean loss over 10 batches for each split, and finally returns the results. The model is then set back to training mode with model.train().

We’re building a basic neural network that we’ll improve later using LLaMA techniques.

# Definition of a basic neural network class

class SimpleBrokenModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config=MASTER_CONFIG):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Embedding layer to convert character indices to vectors (vocab size: 65)

self.embedding = nn.Embedding(config['vocab_size'], config['d_model'])

# Linear layers for modeling relationships between features

# (to be updated with SwiGLU activation function as in LLaMA)

self.linear = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model']),

nn.ReLU(), # Currently using ReLU, will be replaced with SwiGLU as in LLaMA

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['vocab_size']),

)

# Print the total number of model parameters

print("Model parameters:", sum([m.numel() for m in self.parameters()]))In the current architecture, the embedding layer has a vocabulary size of 65, representing the characters in our dataset. As this serves as our base model, we are using **ReLU **as the activation function in the linear layers; however, this will later be replaced with SwiGLU, as used in LLaMA.

To create a forward pass for our base model, we must define a forward function within our NN model.

# Definition of a basic neural network class

class SimpleBrokenModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config=MASTER_CONFIG):

# Rest of the code

...

# Forward pass function for the base model

def forward(self, idx, targets=None):

# Embedding layer converts character indices to vectors

x = self.embedding(idx)

# Linear layers for modeling relationships between features

a = self.linear(x)

# Apply softmax activation to obtain probability distribution

logits = F.softmax(a, dim=-1)

# If targets are provided, calculate and return the cross-entropy loss

if targets is not None:

# Reshape logits and targets for cross-entropy calculation

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits.view(-1, self.config['vocab_size']), targets.view(-1))

return logits, loss

# If targets are not provided, return the logits

else:

return logits

# Print the total number of model parameters

print("Model parameters:", sum([m.numel() for m in self.parameters()]))This forward pass function takes character indices (idx) as input, applies the embedding layer, passes the result through linear layers, applies a softmax activation to obtain a probability distribution (logits). If targets are provided, it calculates the cross-entropy loss and returns both logits and loss. If targets are not provided, it returns only the logits.

To instantiate this model, we can directly invoke the class and print the total number of parameters in our Simple Neural Network Model. We’ve set the dimension of our linear layers to 128, specifying this value in our config object:

# Update MASTER_CONFIG with the dimension of linear layers (128)

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

'd_model': 128,

})

# Instantiate the SimpleBrokenModel using the updated MASTER_CONFIG

model = SimpleBrokenModel(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Print the total number of parameters in the model

print("Total number of parameters in the Simple Neural Network Model:", sum([m.numel() for m in model.parameters()]))Our Simple Neural Network Model comprises approximately 33,000 parameters.

Similarly, to compute logits and loss, we only need to feed our split dataset into our model:

# Obtain batches for training using the specified batch size and context window

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Calculate logits and loss using the model

logits, loss = model(xs, ys)To train our base model and note its performance, we need to specify some parameters. We are training for a total of 1000 epochs. Increasing the batch size to 32 from 8, and set the log_interval to 10, indicating that the code will print or log information about the training progress every 10 batches. For optimization, we’ll use the Adam optimizer.

# Update MASTER_CONFIG with training parameters

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

'epochs': 1000, # Number of training epochs

'log_interval': 10, # Log information every 10 batches during training

'batch_size': 32, # Increase batch size to 32

})

# Instantiate the SimpleBrokenModel with updated configuration

model = SimpleBrokenModel(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Define the Adam optimizer for model parameters

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(

model.parameters(), # Pass the model parameters to the optimizer

)Let’s execute the training process and capture the loss from our base model, including the total number of parameters. Additionally, each line is commented for clarity:

# Function to perform training

def train(model, optimizer, scheduler=None, config=MASTER_CONFIG, print_logs=False):

# Placeholder for storing losses

losses = []

# Start tracking time

start_time = time.time()

# Iterate through epochs

for epoch in range(config['epochs']):

# Zero out gradients

optimizer.zero_grad()

# Obtain batches for training

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', config['batch_size'], config['context_window'])

# Forward pass through the model to calculate logits and loss

logits, loss = model(xs, targets=ys)

# Backward pass and optimization step

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

# If a learning rate scheduler is provided, adjust the learning rate

if scheduler:

scheduler.step()

# Log progress every specified interval

if epoch % config['log_interval'] == 0:

# Calculate batch time

batch_time = time.time() - start_time

# Evaluate loss on validation set

x = evaluate_loss(model)

# Store the validation loss

losses += [x]

# Print progress logs if specified

if print_logs:

print(f"Epoch {epoch} | val loss {x['val']:.3f} | Time {batch_time:.3f} | ETA in seconds {batch_time * (config['epochs'] - epoch)/config['log_interval'] :.3f}")

# Reset the timer

start_time = time.time()

# Print learning rate if a scheduler is provided

if scheduler:

print("lr: ", scheduler.get_lr())

# Print the final validation loss

print("Validation loss: ", losses[-1]['val'])

# Plot the training and validation loss curves

return pd.DataFrame(losses).plot()

# Execute the training process

train(model, optimizer)The initial cross-entropy loss before training stands at 4.17, and after 1000 epochs, it reduces to 3.93. In this context, cross-entropy reflects the likelihood of selecting the incorrect word.

Our model incorporates a softmax layer on the logits, which transforms a vector of numbers into a probability distribution. Let’s use the built-in F.cross_entropy function, we need to directly pass in the unnormalized logits. Consequently, we will modify our model accordingly.

# Modified SimpleModel class without softmax layer

class SimpleModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

# Rest of the code

...

def forward(self, idx, targets=None):

# Embedding layer converts character indices to vectors

x = self.embedding(idx)

# Linear layers for modeling relationships between features

logits = self.linear(x)

# If targets are provided, calculate and return the cross-entropy loss

if targets is not None:

# Rest of the code

...Let’s recreate the updated SimpleModel and train it for 1000 epochs to observe any changes:

# Create the updated SimpleModel

model = SimpleModel(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Obtain batches for training

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Calculate logits and loss using the model

logits, loss = model(xs, ys)

# Define the Adam optimizer for model parameters

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters())

# Train the model for 100 epochs

train(model, optimizer)After reducing the loss to 2.51, let’s explore how our language model with approximately 33,000 parameters generates text during inferencing. We’ll create a ‘generate’ function, which we’ll later use when replicating LLaMA:

# Generate function for text generation using the trained model

def generate(model, config=MASTER_CONFIG, max_new_tokens=30):

idx = torch.zeros(5, 1).long()

for _ in range(max_new_tokens):

# Call the model

logits = model(idx[:, -config['context_window']:])

last_time_step_logits = logits[

:, -1, :

] # all the batches (1), last time step, all the logits

p = F.softmax(last_time_step_logits, dim=-1) # softmax to get probabilities

idx_next = torch.multinomial(

p, num_samples=1

) # sample from the distribution to get the next token

idx = torch.cat([idx, idx_next], dim=-1) # append to the sequence

return [decode(x) for x in idx.tolist()]

# Generate text using the trained model

generate(model)The generated text doesn’t look great with our basic model of around 33K parameters. However, now that we’ve laid the groundwork with this simple model, we’ll move on to constructing the LLaMA architecture in the next section.

In the earlier part of the blog, we covered essential concepts, and now, we’ll integrate these concepts into our base model. LLaMA introduces three architectural modifications to the original Transformer:

-

RMSNorm for pre-normalization

-

Rotary embeddings

-

SwiGLU activation function

We’ll incorporate each of these modifications one by one into our base model, iterating and building upon them.

We are defining an RMSNorm function with the following functionalities:

class RMSNorm(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, layer_shape, eps=1e-8, bias=False):

super(RMSNorm, self).__init__()

# Registering a learnable parameter 'scale' as a parameter of the module

self.register_parameter("scale", nn.Parameter(torch.ones(layer_shape)))

def forward(self, x):

"""

Assumes shape is (batch, seq_len, d_model)

"""

# Calculating the Frobenius norm, RMS = 1/sqrt(N) * Frobenius norm

ff_rms = torch.linalg.norm(x, dim=(1,2)) * x[0].numel() ** -.5

# Normalizing the input tensor 'x' with respect to RMS

raw = x / ff_rms.unsqueeze(-1).unsqueeze(-1)

# Scaling the normalized tensor using the learnable parameter 'scale'

return self.scale[:x.shape[1], :].unsqueeze(0) * rawwe define the RMSNorm class. During initialization, it registers a scale parameter. In the forward pass, it calculates the Frobenius norm of the input tensor and then normalizes the tensor. Finally, the tensor is scaled by the registered scale parameter. This function is designed for use in LLaMA to replace the LayerNorm operation.

Now it’s time to incorporate the first implementation concept of LLaMA, which is RMSNorm, into our simple NN model. Here’s the updated code:

# Define the SimpleModel_RMS with RMSNorm

class SimpleModel_RMS(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Embedding layer to convert character indices to vectors

self.embedding = nn.Embedding(config['vocab_size'], config['d_model'])

# RMSNorm layer for pre-normalization

self.rms = RMSNorm((config['context_window'], config['d_model']))

# Linear layers for modeling relationships between features

self.linear = nn.Sequential(

# Rest of the code

...

)

# Print the total number of model parameters

print("Model parameters:", sum([m.numel() for m in self.parameters()]))

def forward(self, idx, targets=None):

# Embedding layer converts character indices to vectors

x = self.embedding(idx)

# RMSNorm pre-normalization

x = self.rms(x)

# Linear layers for modeling relationships between features

logits = self.linear(x)

if targets is not None:

# Rest of the code

...Let’s execute the modified NN model with RMSNorm and observe the updated number of parameters in the model, along with the loss:

# Create an instance of SimpleModel_RMS

model = SimpleModel_RMS(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Obtain batches for training

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Calculate logits and loss using the model

logits, loss = model(xs, ys)

# Define the Adam optimizer for model parameters

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters())

# Train the model

train(model, optimizer)The validation loss experiences a small decrease, and the parameters of our updated LLM now total approximately 55,000.

Next, we will implement rotary positional embeddings. In RoPE, the authors suggest embedding the position of a token in a sequence by rotating the embedding, applying a different rotation at each position. Let’s create a function that mimics the actual paper implementation of RoPE:

def get_rotary_matrix(context_window, embedding_dim):

# Initialize a tensor for the rotary matrix with zeros

R = torch.zeros((context_window, embedding_dim, embedding_dim), requires_grad=False)

# Loop through each position in the context window

for position in range(context_window):

# Loop through each dimension in the embedding

for i in range(embedding_dim // 2):

# Calculate the rotation angle (theta) based on the position and embedding dimension

theta = 10000. ** (-2. * (i - 1) / embedding_dim)

# Calculate the rotated matrix elements using sine and cosine functions

m_theta = position * theta

R[position, 2 * i, 2 * i] = np.cos(m_theta)

R[position, 2 * i, 2 * i + 1] = -np.sin(m_theta)

R[position, 2 * i + 1, 2 * i] = np.sin(m_theta)

R[position, 2 * i + 1, 2 * i + 1] = np.cos(m_theta)

return Rwe generate a rotary matrix based on the specified context window and embedding dimension, following the proposed RoPE implementation.

As you may be familiar with the architecture of transformers, which involves attention heads, we similarly need to create attention heads when replicating LLaMA. To start, let’s first create a single masked attention head using the get_rotary_matrix function we previously developed for rotary embeddings. Additionally, each line is commented for clarity:

class RoPEAttentionHead(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Linear transformation for query

self.w_q = nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model'], bias=False)

# Linear transformation for key

self.w_k = nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model'], bias=False)

# Linear transformation for value

self.w_v = nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model'], bias=False)

# Obtain rotary matrix for positional embeddings

self.R = get_rotary_matrix(config['context_window'], config['d_model'])

def get_rotary_matrix(context_window, embedding_dim):

# Generate rotational matrix for RoPE

R = torch.zeros((context_window, embedding_dim, embedding_dim), requires_grad=False)

for position in range(context_window):

for i in range(embedding_dim//2):

# Rest of the code

...

return R

def forward(self, x, return_attn_weights=False):

# x: input tensor of shape (batch, sequence length, dimension)

b, m, d = x.shape # batch size, sequence length, dimension

# Linear transformations for Q, K, and V

q = self.w_q(x)

k = self.w_k(x)

v = self.w_v(x)

# Rotate Q and K using the RoPE matrix

q_rotated = (torch.bmm(q.transpose(0, 1), self.R[:m])).transpose(0, 1)

k_rotated = (torch.bmm(k.transpose(0, 1), self.R[:m])).transpose(0, 1)

# Perform scaled dot-product attention

activations = F.scaled_dot_product_attention(

q_rotated, k_rotated, v, dropout_p=0.1, is_causal=True

)

if return_attn_weights:

# Create a causal attention mask

attn_mask = torch.tril(torch.ones((m, m)), diagonal=0)

# Calculate attention weights and add causal mask

attn_weights = torch.bmm(q_rotated, k_rotated.transpose(1, 2)) / np.sqrt(d) + attn_mask

attn_weights = F.softmax(attn_weights, dim=-1)

return activations, attn_weights

return activationsNow that we have a single masked attention head that returns attention weights, the next step is to create a multi-Head attention mechanism.

class RoPEMaskedMultiheadAttention(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Create a list of RoPEMaskedAttentionHead instances as attention heads

self.heads = nn.ModuleList([

RoPEMaskedAttentionHead(config) for _ in range(config['n_heads'])

])

self.linear = nn.Linear(config['n_heads'] * config['d_model'], config['d_model']) # Linear layer after concatenating heads

self.dropout = nn.Dropout(.1) # Dropout layer

def forward(self, x):

# x: input tensor of shape (batch, sequence length, dimension)

# Process each attention head and concatenate the results

heads = [h(x) for h in self.heads]

x = torch.cat(heads, dim=-1)

# Apply linear transformation to the concatenated output

x = self.linear(x)

# Apply dropout

x = self.dropout(x)

return xThe original paper used 32 heads for their smaller 7b LLM variation, but due to constraints, we’ll use 8 heads for our approach.

# Update the master configuration with the number of attention heads

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

'n_heads': 8,

})Now that we’ve implemented Rotational Embedding and Multi-head Attention, let’s re-write our RMSNorm neural network model with the updated code. We’ll test its performance, compute the loss, and check the number of parameters. We’ll refer to this updated model as “RopeModel”

class RopeModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Embedding layer for input tokens

self.embedding = nn.Embedding(config['vocab_size'], config['d_model'])

# RMSNorm layer for pre-normalization

self.rms = RMSNorm((config['context_window'], config['d_model']))

# RoPEMaskedMultiheadAttention layer

self.rope_attention = RoPEMaskedMultiheadAttention(config)

# Linear layer followed by ReLU activation

self.linear = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model']),

nn.ReLU(),

)

# Final linear layer for prediction

self.last_linear = nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['vocab_size'])

print("model params:", sum([m.numel() for m in self.parameters()]))

def forward(self, idx, targets=None):

# idx: input indices

x = self.embedding(idx)

# One block of attention

x = self.rms(x) # RMS pre-normalization

x = x + self.rope_attention(x)

x = self.rms(x) # RMS pre-normalization

x = x + self.linear(x)

logits = self.last_linear(x)

if targets is not None:

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits.view(-1, self.config['vocab_size']), targets.view(-1))

return logits, loss

else:

return logitsLet’s execute the modified NN model with RMSNorm, Rotational Embeddings and Masked Multi Head Attentions to observe the updated number of parameters in the model, along with the loss:

# Create an instance of RopeModel (RMSNorm, RoPE, Multi-Head)

model = RopeModel(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Obtain batches for training

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Calculate logits and loss using the model

logits, loss = model(xs, ys)

# Define the Adam optimizer for model parameters

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters())

# Train the model

train(model, optimizer)The validation loss experiences a small decrease again, and the parameters of our updated LLM now total approximately 55,000.

Let’s train the model for more epochs to see if the loss of our recreated LLaMA LLM continues to decrease or not.

# Updating training configuration with more epochs and a logging interval

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

"epochs": 5000,

"log_interval": 10,

})

# Training the model with the updated configuration

train(model, optimizer)The validation loss continues to decrease, suggesting that training for more epochs could lead to further loss reduction, though not significantly.

As mentioned before, the creators of LLaMA use SwiGLU instead of ReLU, so we’ll be implementing SwiGLU equation in our code.

class SwiGLU(nn.Module):

""" Paper Link -> https://arxiv.org/pdf/2002.05202v1.pdf """

def __init__(self, size):

super().__init__()

self.config = config # Configuration information

self.linear_gate = nn.Linear(size, size) # Linear transformation for the gating mechanism

self.linear = nn.Linear(size, size) # Linear transformation for the main branch

self.beta = torch.randn(1, requires_grad=True) # Random initialization of the beta parameter

# Using nn.Parameter for beta to ensure it's recognized as a learnable parameter

self.beta = nn.Parameter(torch.ones(1))

self.register_parameter("beta", self.beta)

def forward(self, x):

# Swish-Gated Linear Unit computation

swish_gate = self.linear_gate(x) * torch.sigmoid(self.beta * self.linear_gate(x))

out = swish_gate * self.linear(x) # Element-wise multiplication of the gate and main branch

return outAfter implementing the SwiGLU equation in python, we need to integrate it into our modified LLaMA language model (RopeModel).

class RopeModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Embedding layer for input tokens

self.embedding = nn.Embedding(config['vocab_size'], config['d_model'])

# RMSNorm layer for pre-normalization

self.rms = RMSNorm((config['context_window'], config['d_model']))

# Multi-head attention layer with RoPE (Rotary Positional Embeddings)

self.rope_attention = RoPEMaskedMultiheadAttention(config)

# Linear layer followed by SwiGLU activation

self.linear = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model']),

SwiGLU(config['d_model']), # Adding SwiGLU activation

)

# Output linear layer

self.last_linear = nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['vocab_size'])

# Printing total model parameters

print("model params:", sum([m.numel() for m in self.parameters()]))

def forward(self, idx, targets=None):

x = self.embedding(idx)

# One block of attention

x = self.rms(x) # RMS pre-normalization

x = x + self.rope_attention(x)

x = self.rms(x) # RMS pre-normalization

x = x + self.linear(x) # Applying SwiGLU activation

logits = self.last_linear(x)

if targets is not None:

# Calculate cross-entropy loss if targets are provided

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits.view(-1, self.config['vocab_size']), targets.view(-1))

return logits, loss

else:

return logitsLet’s execute the modified NN model with RMSNorm, Rotational Embeddings, Masked Multi Head Attentions and SwiGLU to observe the updated number of parameters in the model, along with the loss:

# Create an instance of RopeModel (RMSNorm, RoPE, Multi-Head, SwiGLU)

model = RopeModel(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Obtain batches for training

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Calculate logits and loss using the model

logits, loss = model(xs, ys)

# Define the Adam optimizer for model parameters

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters())

# Train the model

train(model, optimizer)Once again the validation loss experiences a small decrease, and the parameters of our updated LLM now total approximately 60,000.

So far, we have successfully implemented the key components of the paper, namely RMSNorm, RoPE, and SwiGLU. We observed that these implementations led to a minimal decrease in the loss.

Now we will add layers to our LLaMA to examine its impact on the loss. The original paper used 32 layers for the 7b version, but we will use only 4 layers. Let’s adjust our model settings accordingly.

# Update model configurations for the number of layers

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

'n_layers': 4, # Set the number of layers to 4

})Let’s start by creating a single layer to understand its impact.

# add RMSNorm and residual connection

class LlamaBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# RMSNorm layer

self.rms = RMSNorm((config['context_window'], config['d_model']))

# RoPE Masked Multihead Attention layer

self.attention = RoPEMaskedMultiheadAttention(config)

# Feedforward layer with SwiGLU activation

self.feedforward = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model']),

SwiGLU(config['d_model']),

)

def forward(self, x):

# one block of attention

x = self.rms(x) # RMS pre-normalization

x = x + self.attention(x) # residual connection

x = self.rms(x) # RMS pre-normalization

x = x + self.feedforward(x) # residual connection

return xCreate an instance of the LlamaBlock class and applies it to a random tensor.

# Create an instance of the LlamaBlock class with the provided configuration

block = LlamaBlock(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Generate a random tensor with the specified batch size, context window, and model dimension

random_input = torch.randn(MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'], MASTER_CONFIG['d_model'])

# Apply the LlamaBlock to the random input tensor

output = block(random_input)Having successfully created a single layer, we can now use it to construct multiple layers. Additionally, we will rename our model class from “ropemodel” to “Llama” as we have replicated every component of the LLaMA language model.

class Llama(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, config):

super().__init__()

self.config = config

# Embedding layer for token representations

self.embeddings = nn.Embedding(config['vocab_size'], config['d_model'])

# Sequential block of LlamaBlocks based on the specified number of layers

self.llama_blocks = nn.Sequential(

OrderedDict([(f"llama_{i}", LlamaBlock(config)) for i in range(config['n_layers'])])

)

# Feedforward network (FFN) for final output

self.ffn = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['d_model']),

SwiGLU(config['d_model']),

nn.Linear(config['d_model'], config['vocab_size']),

)

# Print total number of parameters in the model

print("model params:", sum([m.numel() for m in self.parameters()]))

def forward(self, idx, targets=None):

# Input token indices are passed through the embedding layer

x = self.embeddings(idx)

# Process the input through the LlamaBlocks

x = self.llama_blocks(x)

# Pass the processed input through the final FFN for output logits

logits = self.ffn(x)

# If targets are not provided, return only the logits

if targets is None:

return logits

# If targets are provided, compute and return the cross-entropy loss

else:

loss = F.cross_entropy(logits.view(-1, self.config['vocab_size']), targets.view(-1))

return logits, lossLet’s execute the modified LLaMA model with RMSNorm, Rotational Embeddings, Masked Multi Head Attentions, SwiGLU and N_layers to observe the updated number of parameters in the model, along with the loss:

# Create an instance of RopeModel (RMSNorm, RoPE, Multi-Head, SwiGLU, N_layers)

llama = Llama(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Obtain batches for training

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'train', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Calculate logits and loss using the model

logits, loss = llama(xs, ys)

# Define the Adam optimizer for model parameters

optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(llama.parameters())

# Train the model

train(llama, optimizer)While there’s a possibility of overfitting, it’s crucial to explore whether extending the number of epochs leads to a further reduction in loss. Additionally, note that our current LLM has over 2 million parameters.

Let’s train it for higher number of epochs.

# Update the number of epochs in the configuration

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

'epochs': 10000,

})

# Train the LLaMA model for the specified number of epochs

train(llama, optimizer, scheduler=None, config=MASTER_CONFIG)The loss here is 1.08, we can achieve even more lower loss without encountering significant overfitting. This suggests the model is performing well.

Let’s train the model once more, this time incorporating a scheduler

# Training the model again, scheduler for better optimization.

train(llama, optimizer, config=MASTER_CONFIG)Up until now, we’ve successfully implemented a scaled-down version of the LLaMA architecture on our custom dataset. Now, let’s examine the generated output from our 2 million-parameter Language Model.

# Generate text using the trained LLM (llama) with a maximum of 500 tokens

generated_text = generate(llama, MASTER_CONFIG, 500)[0]

print(generated_text)

Even though some generated words may not be perfect English, our LLM with just 2 million parameters has shown a basic understanding of the English language.

Now, let’s see how well our model performs on the test set.

# Get batches from the test set

xs, ys = get_batches(dataset, 'test', MASTER_CONFIG['batch_size'], MASTER_CONFIG['context_window'])

# Pass the test data through the LLaMA model

logits, loss = llama(xs, ys)

# Print the loss on the test set

print(loss)The computed loss on the test set is approximately 1.236.

A simple way to check for changes in the generated output is to run training for a large number of epochs and observe the results.

Hyperparameter tuning is a crucial step in training neural networks. In the original Llama paper, the authors utilized the Cosine Annealing learning schedule. However, in our experimentation, it didn’t perform well. Here’s an example of experimenting with hyperparameters using a different learning schedule:

# Update configuration

MASTER_CONFIG.update({

"epochs": 1000

})

# Create Llama model with Cosine Annealing learning schedule

llama_with_cosine = Llama(MASTER_CONFIG)

# Define Adam optimizer with specific hyperparameters

llama_optimizer = torch.optim.Adam(

llama.parameters(),

betas=(.9, .95),

weight_decay=.1,

eps=1e-9,

lr=1e-3

)

# Define Cosine Annealing learning rate scheduler

scheduler = torch.optim.lr_scheduler.CosineAnnealingLR(llama_optimizer, 300, eta_min=1e-5)

# Train the Llama model with the specified optimizer and scheduler

train(llama_with_cosine, llama_optimizer, scheduler=scheduler)You can save your entire LLM or just the parameters using the following:

# Save the entire model

torch.save(llama, 'llama_model.pth')

# If you want to save only the model parameters

torch.save(llama.state_dict(), 'llama_model_params.pth')To save your PyTorch model for Hugging Face’s Transformers library, you can use the save_pretrained method. Here's an example:

from transformers import GPT2LMHeadModel, GPT2Config

# Assuming Llama is your PyTorch model

llama_config = GPT2Config.from_dict(MASTER_CONFIG)

llama_transformers = GPT2LMHeadModel(config=llama_config)

llama_transformers.load_state_dict(llama.state_dict())

# Specify the directory where you want to save the model

output_dir = "llama_model_transformers"

# Save the model and configuration

llama_transformers.save_pretrained(output_dir)GPT2Config is used to create a configuration object compatible with GPT-2. Then, a GPT2LMHeadModel is created and loaded with the weights from your Llama model. Finally, save_pretrained is called to save both the model and configuration in the specified directory.

You can then load the model using the Transformers library:

from transformers import GPT2LMHeadModel, GPT2Config

# Specify the directory where the model was saved

output_dir = "llama_model_transformers"

# Load the model and configuration

llama_transformers = GPT2LMHeadModel.from_pretrained(output_dir)In this blog, we’ve walked through a step-by-step process on how to implement the LLaMA approach to build your own small Language Model (LLM). As a suggestion, consider expanding your model to around 15 million parameters, as smaller models in the range of 10M to 20M tend to comprehend English better. Once your LLM becomes proficient in language, you can fine-tune it for specific use cases.

I hope this comprehensive blog has provided you with insights on replicating a paper to create your personalized LLM.

Thanks for reading this extensive post!

For Tasks:

Click tags to check more tools for each tasksFor Jobs:

Alternative AI tools for create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch

Similar Open Source Tools

create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch

The 'create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch' repository provides a detailed guide on creating a Large Language Model (LLM) with 2.3 million parameters from scratch. The blog replicates the LLaMA approach, incorporating concepts like RMSNorm for pre-normalization, SwiGLU activation function, and Rotary Embeddings. The model is trained on a basic dataset to demonstrate the ease of creating a million-parameter LLM without the need for a high-end GPU.

zeta

Zeta is a tool designed to build state-of-the-art AI models faster by providing modular, high-performance, and scalable building blocks. It addresses the common issues faced while working with neural nets, such as chaotic codebases, lack of modularity, and low performance modules. Zeta emphasizes usability, modularity, and performance, and is currently used in hundreds of models across various GitHub repositories. It enables users to prototype, train, optimize, and deploy the latest SOTA neural nets into production. The tool offers various modules like FlashAttention, SwiGLUStacked, RelativePositionBias, FeedForward, BitLinear, PalmE, Unet, VisionEmbeddings, niva, FusedDenseGELUDense, FusedDropoutLayerNorm, MambaBlock, Film, hyper_optimize, DPO, and ZetaCloud for different tasks in AI model development.

Gemini

Gemini is an open-source model designed to handle multiple modalities such as text, audio, images, and videos. It utilizes a transformer architecture with special decoders for text and image generation. The model processes input sequences by transforming them into tokens and then decoding them to generate image outputs. Gemini differs from other models by directly feeding image embeddings into the transformer instead of using a visual transformer encoder. The model also includes a component called Codi for conditional generation. Gemini aims to effectively integrate image, audio, and video embeddings to enhance its performance.

Quantus

Quantus is a toolkit designed for the evaluation of neural network explanations. It offers more than 30 metrics in 6 categories for eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) evaluation. The toolkit supports different data types (image, time-series, tabular, NLP) and models (PyTorch, TensorFlow). It provides built-in support for explanation methods like captum, tf-explain, and zennit. Quantus is under active development and aims to provide a comprehensive set of quantitative evaluation metrics for XAI methods.

gem

GEM is an open-source General Experience Maker designed for training Large Language Models (LLMs) in dynamic environments. Similar to OpenAI Gym for traditional Reinforcement Learning, GEM provides a variety of environments with standardized interfaces for seamless integration with existing LLM training frameworks. It offers tool integration, flexible wrappers, async vectorized environment execution, multi-environment training, and more to simplify LLM agent training.

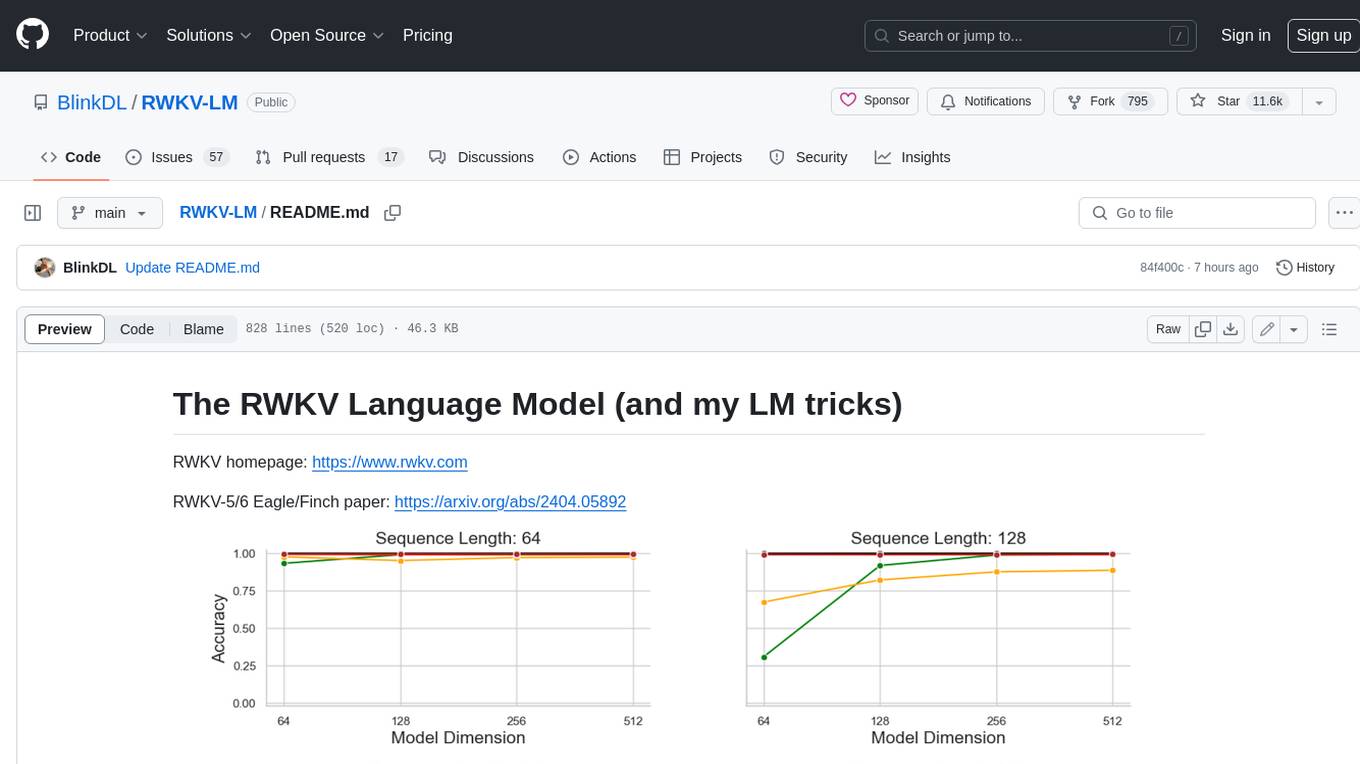

RWKV-LM

RWKV is an RNN with Transformer-level LLM performance, which can also be directly trained like a GPT transformer (parallelizable). And it's 100% attention-free. You only need the hidden state at position t to compute the state at position t+1. You can use the "GPT" mode to quickly compute the hidden state for the "RNN" mode. So it's combining the best of RNN and transformer - **great performance, fast inference, saves VRAM, fast training, "infinite" ctx_len, and free sentence embedding** (using the final hidden state).

SemanticKernel.Assistants

This repository contains an assistant proposal for the Semantic Kernel, allowing the usage of assistants without relying on OpenAI Assistant APIs. It runs locally planners and plugins for the assistants, providing scenarios like Assistant with Semantic Kernel plugins, Multi-Assistant conversation, and AutoGen conversation. The Semantic Kernel is a lightweight SDK enabling integration of AI Large Language Models with conventional programming languages, offering functions like semantic functions, native functions, and embeddings-based memory. Users can bring their own model for the assistants and host them locally. The repository includes installation instructions, usage examples, and information on creating new conversation threads with the assistant.

embodied-agents

Embodied Agents is a toolkit for integrating large multi-modal models into existing robot stacks with just a few lines of code. It provides consistency, reliability, scalability, and is configurable to any observation and action space. The toolkit is designed to reduce complexities involved in setting up inference endpoints, converting between different model formats, and collecting/storing datasets. It aims to facilitate data collection and sharing among roboticists by providing Python-first abstractions that are modular, extensible, and applicable to a wide range of tasks. The toolkit supports asynchronous and remote thread-safe agent execution for maximal responsiveness and scalability, and is compatible with various APIs like HuggingFace Spaces, Datasets, Gymnasium Spaces, Ollama, and OpenAI. It also offers automatic dataset recording and optional uploads to the HuggingFace hub.

beyondllm

Beyond LLM offers an all-in-one toolkit for experimentation, evaluation, and deployment of Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems. It simplifies the process with automated integration, customizable evaluation metrics, and support for various Large Language Models (LLMs) tailored to specific needs. The aim is to reduce LLM hallucination risks and enhance reliability.

pywhy-llm

PyWhy-LLM is an innovative library that integrates Large Language Models (LLMs) into the causal analysis process, empowering users with knowledge previously only available through domain experts. It seamlessly augments existing causal inference processes by suggesting potential confounders, relationships between variables, backdoor sets, front door sets, IV sets, estimands, critiques of DAGs, latent confounders, and negative controls. By leveraging LLMs and formalizing human-LLM collaboration, PyWhy-LLM aims to enhance causal analysis accessibility and insight.

RPG-DiffusionMaster

This repository contains the official implementation of RPG, a powerful training-free paradigm for text-to-image generation and editing. RPG utilizes proprietary or open-source MLLMs as prompt recaptioner and region planner with complementary regional diffusion. It achieves state-of-the-art results and can generate high-resolution images. The codebase supports diffusers and various diffusion backbones, including SDXL and SD v1.4/1.5. Users can reproduce results with GPT-4, Gemini-Pro, or local MLLMs like miniGPT-4. The repository provides tools for quick start, regional diffusion with GPT-4, and regional diffusion with local LLMs.

MotionLLM

MotionLLM is a framework for human behavior understanding that leverages Large Language Models (LLMs) to jointly model videos and motion sequences. It provides a unified training strategy, dataset MoVid, and MoVid-Bench for evaluating human behavior comprehension. The framework excels in captioning, spatial-temporal comprehension, and reasoning abilities.

RTL-Coder

RTL-Coder is a tool designed to outperform GPT-3.5 in RTL code generation by providing a fully open-source dataset and a lightweight solution. It targets Verilog code generation and offers an automated flow to generate a large labeled dataset with over 27,000 diverse Verilog design problems and answers. The tool addresses the data availability challenge in IC design-related tasks and can be used for various applications beyond LLMs. The tool includes four RTL code generation models available on the HuggingFace platform, each with specific features and performance characteristics. Additionally, RTL-Coder introduces a new LLM training scheme based on code quality feedback to further enhance model performance and reduce GPU memory consumption.

inspectus

Inspectus is a versatile visualization tool for large language models. It provides multiple views, including Attention Matrix, Query Token Heatmap, Key Token Heatmap, and Dimension Heatmap, to offer insights into language model behaviors. Users can interact with the tool in Jupyter notebooks through an easy-to-use Python API. Inspectus allows users to visualize attention scores between tokens, analyze how tokens focus on each other during processing, and explore the relationships between query and key tokens. The tool supports the visualization of attention maps from Huggingface transformers and custom attention maps, making it a valuable resource for researchers and developers working with language models.

pywhyllm

PyWhy-LLM is an innovative library that integrates Large Language Models (LLMs) into the causal analysis process, empowering users with knowledge previously only available through domain experts. It seamlessly augments causal inference by suggesting potential confounders, relationships between variables, backdoor/frontdoor/iv sets, estimands, critiques of DAGs, latent confounders, and negative controls. The tool aims to enhance the causal analysis process by leveraging the capabilities of LLMs.

For similar tasks

lighteval

LightEval is a lightweight LLM evaluation suite that Hugging Face has been using internally with the recently released LLM data processing library datatrove and LLM training library nanotron. We're releasing it with the community in the spirit of building in the open. Note that it is still very much early so don't expect 100% stability ^^' In case of problems or question, feel free to open an issue!

Firefly

Firefly is an open-source large model training project that supports pre-training, fine-tuning, and DPO of mainstream large models. It includes models like Llama3, Gemma, Qwen1.5, MiniCPM, Llama, InternLM, Baichuan, ChatGLM, Yi, Deepseek, Qwen, Orion, Ziya, Xverse, Mistral, Mixtral-8x7B, Zephyr, Vicuna, Bloom, etc. The project supports full-parameter training, LoRA, QLoRA efficient training, and various tasks such as pre-training, SFT, and DPO. Suitable for users with limited training resources, QLoRA is recommended for fine-tuning instructions. The project has achieved good results on the Open LLM Leaderboard with QLoRA training process validation. The latest version has significant updates and adaptations for different chat model templates.

Awesome-Text2SQL

Awesome Text2SQL is a curated repository containing tutorials and resources for Large Language Models, Text2SQL, Text2DSL, Text2API, Text2Vis, and more. It provides guidelines on converting natural language questions into structured SQL queries, with a focus on NL2SQL. The repository includes information on various models, datasets, evaluation metrics, fine-tuning methods, libraries, and practice projects related to Text2SQL. It serves as a comprehensive resource for individuals interested in working with Text2SQL and related technologies.

create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch

The 'create-million-parameter-llm-from-scratch' repository provides a detailed guide on creating a Large Language Model (LLM) with 2.3 million parameters from scratch. The blog replicates the LLaMA approach, incorporating concepts like RMSNorm for pre-normalization, SwiGLU activation function, and Rotary Embeddings. The model is trained on a basic dataset to demonstrate the ease of creating a million-parameter LLM without the need for a high-end GPU.

StableToolBench

StableToolBench is a new benchmark developed to address the instability of Tool Learning benchmarks. It aims to balance stability and reality by introducing features such as a Virtual API System with caching and API simulators, a new set of solvable queries determined by LLMs, and a Stable Evaluation System using GPT-4. The Virtual API Server can be set up either by building from source or using a prebuilt Docker image. Users can test the server using provided scripts and evaluate models with Solvable Pass Rate and Solvable Win Rate metrics. The tool also includes model experiments results comparing different models' performance.

BetaML.jl

The Beta Machine Learning Toolkit is a package containing various algorithms and utilities for implementing machine learning workflows in multiple languages, including Julia, Python, and R. It offers a range of supervised and unsupervised models, data transformers, and assessment tools. The models are implemented entirely in Julia and are not wrappers for third-party models. Users can easily contribute new models or request implementations. The focus is on user-friendliness rather than computational efficiency, making it suitable for educational and research purposes.

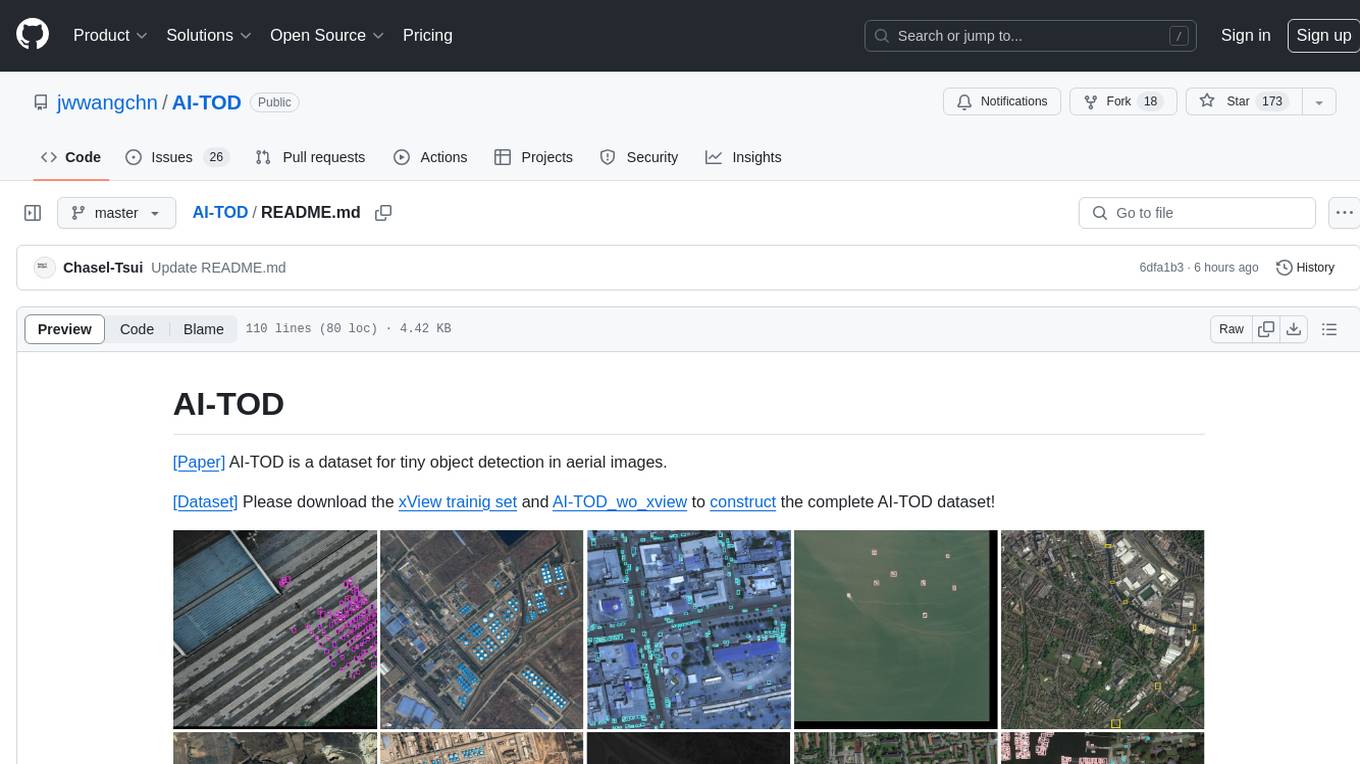

AI-TOD

AI-TOD is a dataset for tiny object detection in aerial images, containing 700,621 object instances across 28,036 images. Objects in AI-TOD are smaller with a mean size of 12.8 pixels compared to other aerial image datasets. To use AI-TOD, download xView training set and AI-TOD_wo_xview, then generate the complete dataset using the provided synthesis tool. The dataset is publicly available for academic and research purposes under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

UMOE-Scaling-Unified-Multimodal-LLMs

Uni-MoE is a MoE-based unified multimodal model that can handle diverse modalities including audio, speech, image, text, and video. The project focuses on scaling Unified Multimodal LLMs with a Mixture of Experts framework. It offers enhanced functionality for training across multiple nodes and GPUs, as well as parallel processing at both the expert and modality levels. The model architecture involves three training stages: building connectors for multimodal understanding, developing modality-specific experts, and incorporating multiple trained experts into LLMs using the LoRA technique on mixed multimodal data. The tool provides instructions for installation, weights organization, inference, training, and evaluation on various datasets.

For similar jobs

promptflow

**Prompt flow** is a suite of development tools designed to streamline the end-to-end development cycle of LLM-based AI applications, from ideation, prototyping, testing, evaluation to production deployment and monitoring. It makes prompt engineering much easier and enables you to build LLM apps with production quality.

deepeval

DeepEval is a simple-to-use, open-source LLM evaluation framework specialized for unit testing LLM outputs. It incorporates various metrics such as G-Eval, hallucination, answer relevancy, RAGAS, etc., and runs locally on your machine for evaluation. It provides a wide range of ready-to-use evaluation metrics, allows for creating custom metrics, integrates with any CI/CD environment, and enables benchmarking LLMs on popular benchmarks. DeepEval is designed for evaluating RAG and fine-tuning applications, helping users optimize hyperparameters, prevent prompt drifting, and transition from OpenAI to hosting their own Llama2 with confidence.

MegaDetector

MegaDetector is an AI model that identifies animals, people, and vehicles in camera trap images (which also makes it useful for eliminating blank images). This model is trained on several million images from a variety of ecosystems. MegaDetector is just one of many tools that aims to make conservation biologists more efficient with AI. If you want to learn about other ways to use AI to accelerate camera trap workflows, check out our of the field, affectionately titled "Everything I know about machine learning and camera traps".

leapfrogai

LeapfrogAI is a self-hosted AI platform designed to be deployed in air-gapped resource-constrained environments. It brings sophisticated AI solutions to these environments by hosting all the necessary components of an AI stack, including vector databases, model backends, API, and UI. LeapfrogAI's API closely matches that of OpenAI, allowing tools built for OpenAI/ChatGPT to function seamlessly with a LeapfrogAI backend. It provides several backends for various use cases, including llama-cpp-python, whisper, text-embeddings, and vllm. LeapfrogAI leverages Chainguard's apko to harden base python images, ensuring the latest supported Python versions are used by the other components of the stack. The LeapfrogAI SDK provides a standard set of protobuffs and python utilities for implementing backends and gRPC. LeapfrogAI offers UI options for common use-cases like chat, summarization, and transcription. It can be deployed and run locally via UDS and Kubernetes, built out using Zarf packages. LeapfrogAI is supported by a community of users and contributors, including Defense Unicorns, Beast Code, Chainguard, Exovera, Hypergiant, Pulze, SOSi, United States Navy, United States Air Force, and United States Space Force.

llava-docker

This Docker image for LLaVA (Large Language and Vision Assistant) provides a convenient way to run LLaVA locally or on RunPod. LLaVA is a powerful AI tool that combines natural language processing and computer vision capabilities. With this Docker image, you can easily access LLaVA's functionalities for various tasks, including image captioning, visual question answering, text summarization, and more. The image comes pre-installed with LLaVA v1.2.0, Torch 2.1.2, xformers 0.0.23.post1, and other necessary dependencies. You can customize the model used by setting the MODEL environment variable. The image also includes a Jupyter Lab environment for interactive development and exploration. Overall, this Docker image offers a comprehensive and user-friendly platform for leveraging LLaVA's capabilities.

carrot

The 'carrot' repository on GitHub provides a list of free and user-friendly ChatGPT mirror sites for easy access. The repository includes sponsored sites offering various GPT models and services. Users can find and share sites, report errors, and access stable and recommended sites for ChatGPT usage. The repository also includes a detailed list of ChatGPT sites, their features, and accessibility options, making it a valuable resource for ChatGPT users seeking free and unlimited GPT services.

TrustLLM

TrustLLM is a comprehensive study of trustworthiness in LLMs, including principles for different dimensions of trustworthiness, established benchmark, evaluation, and analysis of trustworthiness for mainstream LLMs, and discussion of open challenges and future directions. Specifically, we first propose a set of principles for trustworthy LLMs that span eight different dimensions. Based on these principles, we further establish a benchmark across six dimensions including truthfulness, safety, fairness, robustness, privacy, and machine ethics. We then present a study evaluating 16 mainstream LLMs in TrustLLM, consisting of over 30 datasets. The document explains how to use the trustllm python package to help you assess the performance of your LLM in trustworthiness more quickly. For more details about TrustLLM, please refer to project website.

AI-YinMei

AI-YinMei is an AI virtual anchor Vtuber development tool (N card version). It supports fastgpt knowledge base chat dialogue, a complete set of solutions for LLM large language models: [fastgpt] + [one-api] + [Xinference], supports docking bilibili live broadcast barrage reply and entering live broadcast welcome speech, supports Microsoft edge-tts speech synthesis, supports Bert-VITS2 speech synthesis, supports GPT-SoVITS speech synthesis, supports expression control Vtuber Studio, supports painting stable-diffusion-webui output OBS live broadcast room, supports painting picture pornography public-NSFW-y-distinguish, supports search and image search service duckduckgo (requires magic Internet access), supports image search service Baidu image search (no magic Internet access), supports AI reply chat box [html plug-in], supports AI singing Auto-Convert-Music, supports playlist [html plug-in], supports dancing function, supports expression video playback, supports head touching action, supports gift smashing action, supports singing automatic start dancing function, chat and singing automatic cycle swing action, supports multi scene switching, background music switching, day and night automatic switching scene, supports open singing and painting, let AI automatically judge the content.